Eclipses, equinoxes and everyday awe: Telling the time on Spaceship Earth.

Monday, 8 April 2024 — Durango, Mexico

12:12:12 CST 24°01'21.1"N 104°40'17.9"W

All morning Plaza IV Centenario in Durango has been filled as if for a festival. Earlier, a shockingly youthful shaman led a salute to the sun and then gave copal cleansings to a patient queue of hundreds. Local news crews interview anyone and everyone. The chatter feels like nervous laughter before a curtain rises, and we’re all taking selfies in our cardboard eclipse spectacles. I also try peering at the sun through my obsidian medallion, bought the previous week from a hawker in the shadow of the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan. The modern version is more effective, but the obsidian feels truer to the moment.

The start is gradual until it isn’t. When totality comes at 12:12 local time, the sky dims faster and faster. And suddenly there is a ring of fire, a diamond studded loop around a black coin, and the square, the town, the whole country, falls away. For a few minutes I wasn’t in Durango at all. I was on a small sphere moving through the vastness of space.

Totality performs a profound magic trick: it makes the Sun seem small. By hiding its brilliant fire, it seems just another star in our galactic quadrant. The Moon - so familiar, transforms into a lens into time itself. Time stretches. I think about the people who stood on that land thousands of years ago, watching a daytime nightfall and feeling the same cold rush along their arms.

I'm thinking of the heyday of the pyramids at Teotihuacan 1500 years ago and of their tiny Northern cousin at Ferreria, 15 minutes outside Durango that we'd visited the day before. It's closed today because Mondays are always closed. I'm thinking of Stonehenge and further back into deep time of the kind that galaxies tend to operate one. I'm thinking of Transition by Iain Banks and secretly hoping that thrill seeking aliens might be in town for the event. Eclipses like ours are rare in the universe - you need your moon to be juuuust the right size. Except in that moment, I'm not really thinking at all, I'm just enjoying the light show and the vertigo. Delighted that my eclipse experience has been so cosmic.

When the shadow passes, I wonder: How do you keep that feeling when the world returns to normal brightness? How do you make cosmic awe part of the everyday? It is easier than you think...

More moons, more magick

In my view, there are three ways to gain a mind as wide as the sky.

- Find God

- Find nirvana

- Find a firm place to stand and try move the earth.

I will leave the first and second as an exercise for the reader. Instead, let's move the earth. The trick is to properly realise that the earth is already moving.

In this day and age, we all know this intellectually but rarely do we feel it cosmically. Knowledge alone is not our firm place to stand. We need experiences that connect us personally to the cosmic.

I found my way here thanks to ancient solstices at Stonehenge, modern ones on Hackney Marshes, wassails with Brixton morris dancers and magical portals with my serendipity coach. That is a story for another time. The short version is that, in the last couple of years, I've found my way to rituals that make the solar cycles visible again—solstices, full moons, watching how the light shifts with the season. The more I show up for those moments, the more I crave a daily way to remember that we're moving. Something that flips the illusory sweep of the sun across the sky into the reality of the turning of the earth.

Decorating your volcano lair

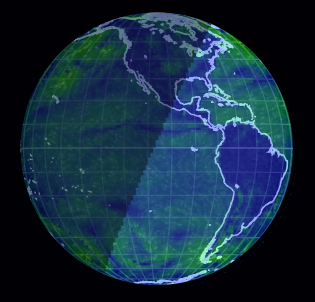

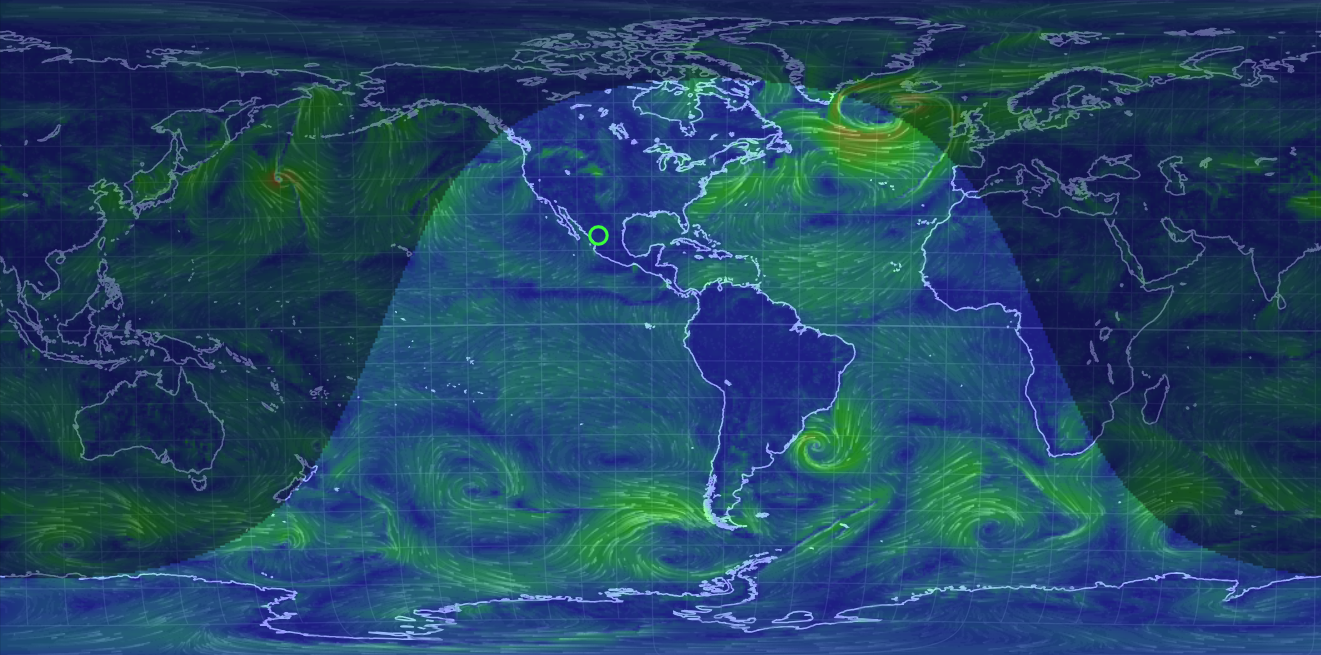

The best way to do this is to become an astronaut, as Samantha Harvey's Orbital expertly evokes. But even for the earthbound, we can take the astronaut's view as a starting point. It leads to a map most of us have only seen as a prop: the rectangular world map on the wall in every movie's NASA control room. Styles vary, but all the best ones have a sinusoidal shadow—what day and night look like flattened from a globe onto an equirectangular projection. The map is a clock.

Stare at it over months and the shape of that band shifts with the season; the sunrise you see is the same sunrise washing across continents, minute by minute. The trouble is, these things are expensive. The artisans at Geochron make beautiful mechanical marvels, but they run $4,600 each. Ersatz supervillain Elon Musk can afford one. I can't.

Screensavers, remember them?

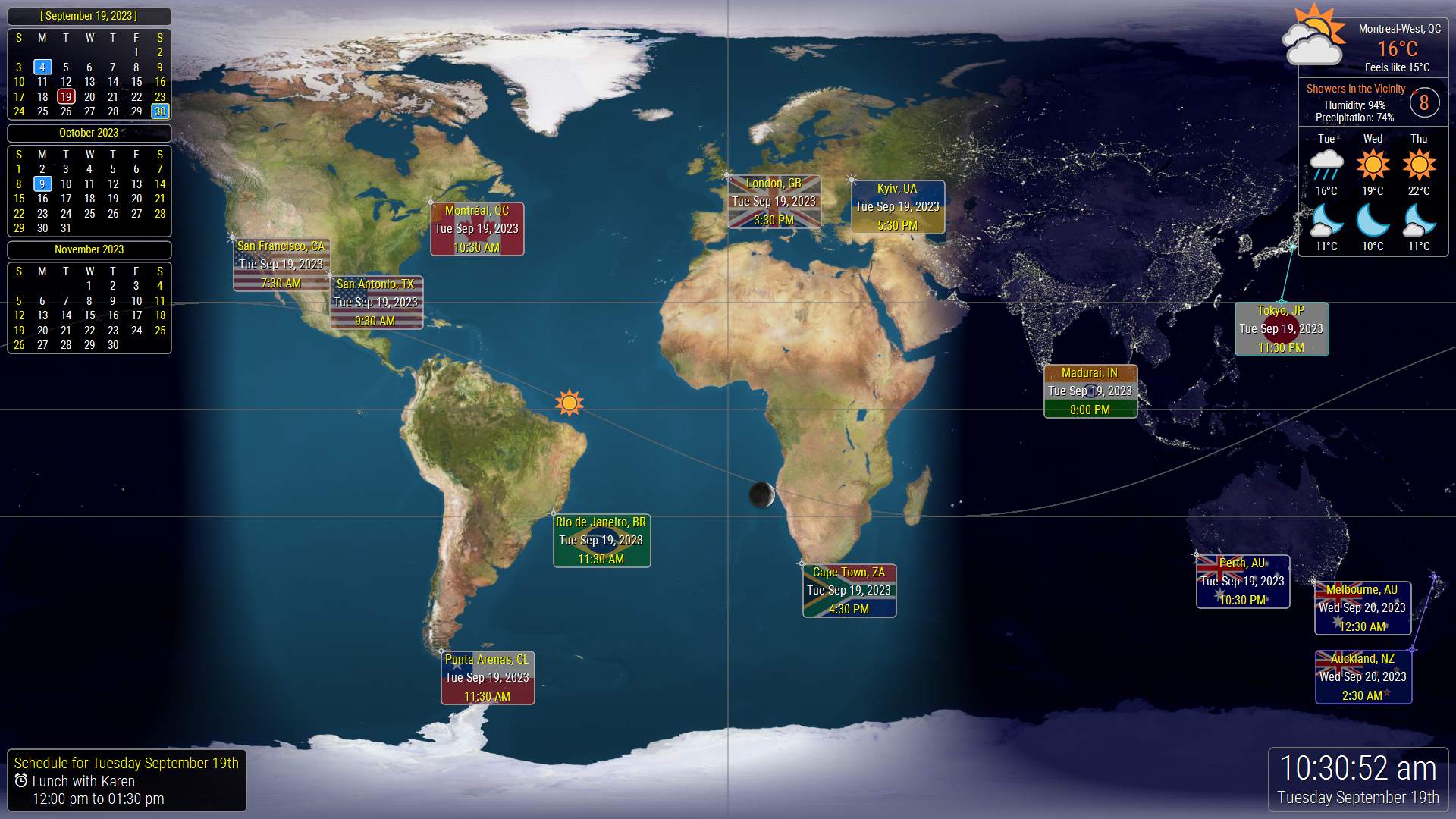

World Clock offers one for $15—more my price bracket. For a while it served me well. I loved how city lights would wink on at night. It showed the moon phases. It gave me, for the first time, a feeling of the whole world at once, gently turning, a soft echo of that eclipse perspective.

But I wanted more. I wanted the whole thing to feel alive, like looking out a window from orbit. I wanted to see the weather we’re all sharing. I wanted the clock to show time with texture, the world’s mood.

I couldn’t find it. So I started sketching.

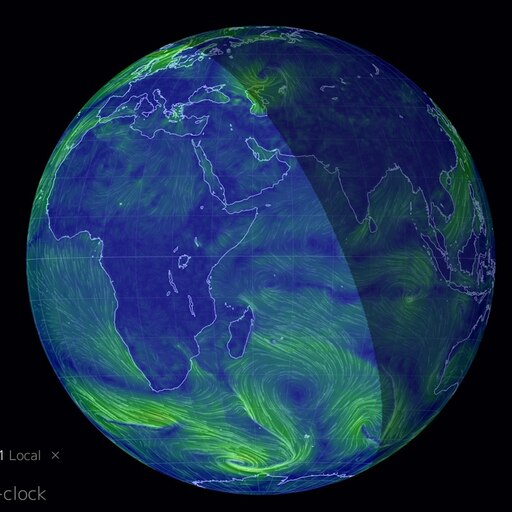

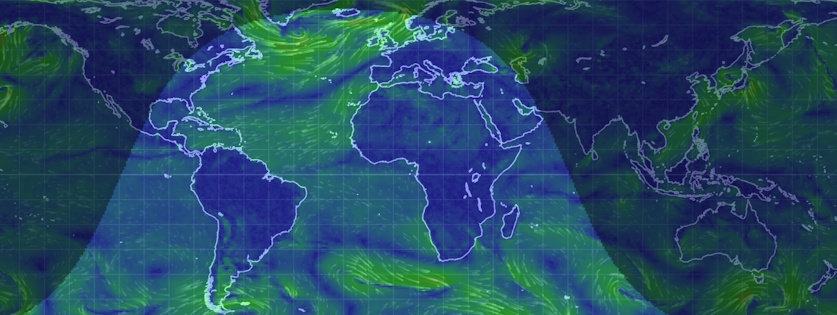

There’s a beloved project called Earth from Nullschool, aka Cameron Becario. It is a living map of winds and currents, with beautiful, swirling vectors and layers for climate patterns. I took that as a base and added the moving shadow of the Sun (the solar terminator) so the day/night line sweeps across the globe in real time. That simple overlay turned the Earth itself into the clock it already is.

Cameron's earth defaults to globe view, but if you switch to an 'equirectangular' projection you have mission control for your bargain basement Bond villain.

You can try it here: http://earth-clock.onemonkey.org/

It’s simple, almost embarrassingly so. I asked the robots to help and they obliged. The first version shows the terminator moving; it breathes with the seasons, lingering over one hemisphere and then the other, stretching and narrowing as the year arcs on. It’s a small thing, but it brings the eclipse back to my breakfast table.

Spaceship Earth

Why does a planetary clock matter? Because a daily glance can do what rare spectacles do—only gently and consistently. Buckminster Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth gave us a framing that feels truer every year: we live on a shared vessel, with finite resources and a common fate. A clock for Spaceship Earth works best as a practice: a small daily act of attention.

It invites you to remember that your morning is someone else’s midnight; your winter is someone else’s summer; your calm sky is someone else’s storm. It makes time empathetic.

There’s a line often attributed to Marshall McLuhan: there are no passengers on Spaceship Earth; we are all crew. A planetary clock is a small crew ritual. It nudges you to look up from the local and notice the ship’s state. It replaces doomscrolling’s crunch of isolated events with a soft, continuous awareness: a storm system spiraling in the Pacific, the monsoon pulse, the slow tilt toward longer days. It doesn’t erase urgency. It locates it in a whole.

If you want to try the practice, here’s what’s worked for me:

- Morning (30 seconds): Open the clock. Notice where the terminator is, where the sunrise is sweeping now. Glance at the winds. Ask: what season is the Earth showing me today?

- Midday (10 seconds): A quick check. Where is it noon? Where is it midnight? Who’s waking up as you log off?

- Evening (30 seconds): Watch the dark advance toward you. Think of the lights coming on across the band of night. Name the weather systems you can see. Close the day with a global view.

Over a few weeks, patterns start to surface without effort:

- The days lengthen, then shorten, a millimeter at a time.

- The terminator leans, then straightens, with the equinoxes.

- You start to feel the mirror-symmetry between hemispheres—their summers and winters exchanging the Sun’s favor.

- Planetary motion stops being an idea you understand and becomes something you notice.

The tool is still simple, and I want it to grow. A wishlist:

- Live cloud cover, so the weather is truly the weather.

- Nighttime city lights in darkness, to feel the human constellation.

- Seasonal overlays and currents, to make the longer rhythms legible.

- A “year in a minute” loop, so you can watch the planet breathe.

- A pointer to the moon (WorldClock does this very well.)

If this sparks something in you—whether you’re an artist, a scientist, a teacher, or just a curious person—come help. I’d love collaborators who can add data layers, refine the visuals, and imagine uses I haven’t thought of yet. Imagine classrooms starting the day with a glance at the ship. Imagine families checking the solstice together. Imagine the quiet of seeing, every day, that we share one weather.

I’ve been back from Durango for a while now. The eclipse has faded into photographs and stories, but its lesson stayed. That ring of fire turned my head outward. The clock keeps it there. It’s a way to make awe durable to turn a rare astonishment into a daily practice, and a daily practice into care.

Try the clock. See what you notice. And if you can, help make it better.

Clock:

Code:

Wallpaper: